The Canvas of Currency.

Currency would probably be the last thing one would think of in the boundless realm of the arts. Yet, within this mundane tool of exchange comes a surprising canvas linking the nation’s economy with artistic expression. Ornate designs, expansive landscapes, and portraits of influential figures adorn it, creating a visual narrative reflecting our cultural identity shaped by our country’s rich history.

Tracing the roots of Philippine financial history, its currency has long had Spanish icons since their colonization period, typically etchings of royalties from Spain. The circulation of such currency exposed dissonance between the Philippines and its colonizer. The Philippines lacked a tangible connection to the figures fueling a yearning for freedom, self-determination, and identity. The coins as a symbol of authority instead ignited unity which served as a reminder of the distance between the governed and those governing, conflagrating the will of Philippine nationalism.

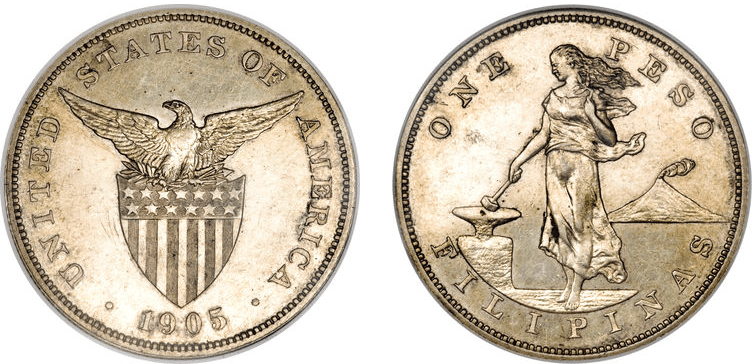

Fifty Centavos and One Peso (Numista, 2023)

When the Americans took over in 1898, they were also relatively new in having national symbols grace their currency. The year 1863 saw them pass a law standardizing the design of all currency in the United States (National Banking Act of 1863). The objective of this law is to ensure the masses would encounter national symbols in their everyday lives, learn about the prominent period in their country’s history, and imbue in them the feeling of nationalism. Currency mark on each citizen the power and glory of a unified nation through its everyday use. Research suggests that this was one of the key pieces of legislation used in determining what symbols and heroes would be placed on the Philippines’ currency.

Because the United States decided to use a separate currency for the Philippines, the designs to be used were that of a unique national identity. The Americans saw that the revolutionary period of the Ilustrados and Katipunan was grounds to create a backdrop for the national mythos. The sacrifice of those who participated would be the first few figures on the currency at the time. They viewed the Philippines as a nation under their tutelage, requiring guidance and oversight. This belief permeated the Philippine Commission and various agencies, influencing their decisions regarding the currency’s design. They envisioned it as a tool to cultivate a Filipino identity.

With the designs in place, everything was set for the “financial artists” of the Philippines from the colonial age to the modern era. The currency’s artistic potential would thus transcend its physical form as this ubiquitous symbol would carry cultural and social weight on the scale of the economic system.

Iloilo to Immortality.

Melecio Figueroa (Raphael Canillas, 2023)

Melecio Figueroa has had a keen eye for the arts and in particular the demanding form of sculpture. Born in May 1842 to a poor Ilonggo family, his early life would be marked by hardship. He would eventually move in with his aunt, Juana Yulo, alongside his younger sister. Now to support her adopted children, Juana would sell Bibingka (rice cakes).Noticing the influx of customers that would swarm his aunt, Melecio’s crafty hand would create wood carvings of flora and fauna and give to each of them. This would be one of his formative years in perfecting his craft.

As he matured physically and in his craft, he garnered the attention of a Spanish businessman, Don Francisco Ahujas. Melecio’s work impressed him so much that he offered him a scholarship to further his education and career in the Spanish tradition. This is the only known instance of a colonialist offering a private scholarship to a Filipino. Arriving in Madrid, Spain in 1866, he would study at the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. Putting his heart and soul into each work required by the institution, Melecio would become an honor student and even appear as a subject of the royal court.

Alas, his luck would run thin as his sponsor would die in the middle of his studies, and would have to work a series of jobs. Things would look bleak to him as he initially worked as a watch repairman but this did not satisfy him as he wanted something closer to his passions. He turned to sculpting to satisfy the desire of his soul and ease his troubles. One of his most recognizable sculptures is a wax bust of King Alfonso XII. The effigy was so magnificent that the Madrid correspondent of the Philippine newspaper El Comercio wrote an article entitled “Un Artista Filipino” dated December 7, 1876. The paper praised him for never letting go of his passions despite the hardship and pouring his soul and emotion into the craft he so loved. The article concluded by challenging the Philippines to provide support to such a distinguished artist and to provide opportunities to those poor Filipinos with exceptional talent.

King Alfonso XII of Spain (Royal Collection Trust, 1875)

The article tugged the strings of the hearts and there was a chain reaction to support him and the artist community. The then Governor-General himself ensured that financial support be sent as a pension de gracia that would last for three years. His school even offered him a fellowship and sent him to Rome to further his education. Melecio would be the only Indio-Filipino to have been honored by the school. At the end of it, he received four scholarships to support him, but most importantly it started a movement in the Philippines to bring locals into the light and perfect their skills.

Melecio would finish his studies and stay in Spain for some time as a celebrated artist, even engraving medals for the Philippine Exposition. His life was full of glamor from high society and the roar of the crowd who admired his work. During one of the Expositions, when introduced to the public, the crowd would cheer and chant his name.

Walking Away.

Despite the attention and praise he received in a foreign country, his heart was yearning for the Philippines. Millions of kilometers away, his land was calling for his return to restore her glory through the arts and revolution. He heeded her call, stepped away from the limelight, and set sail into the loving embrace of his motherland. In 1892, he returned alongside his wife and daughter, Enriqueta and Blanca. With his reputation, he was appointed as a first-class engraver at the Manila Mint and commissioned to prepare designs for the new Philippine coins. He would even become a professor at Liceo De Manila teaching his craft at the school.

He began experimenting with designs that can be traced as far back as the 1880s on his medal engravings. The most notable of the designs would be a beautiful woman. Eventually, his work would be scrapped as the outbreak of the Philippine Revolution of 1896 hindered his progress. Interestingly, he would be a major proponent of the revolution as he would represent Iloilo in the Malolos Convention of 1898.

Chisel to Peso.

During the transition period between the Spanish and the American colonizers, Melecio continued his duties as an engraver and as a professor. There was much debate between the Philippine Commission on the fate of the islands. On one hand, US Imperialists believe that the Philippines is under American rule and should be governed as such. US Anti-Imperialists saw that the Philippines should be given its liberty in due time.

A market or fair (University of Michigan, 1890)

These debates would eventually seep into the design of the new Philippine currency. It was clear that American symbols would be adorned as it was supposed to represent their authority. However, using the lessons the Americans have learned from 1863, who would be the icon to represent the Philippine Islands? The local populace would not be united under a foreign symbol and was simply not their culture. Given that the Philippines was to have a separate currency, the designs could express a distinct national identity.

The U.S. colonial government took advantage of the situation and created a new national myth that recognized the revolutionary years of 1896-1898 as having produced a “fledgling nation.” The colonial government aimed to shape Filipino national identity and strengthen the new nation’s colonial relationship with the United States through the designs of the U.S.-Philippine currency. The Philippine Commission set out to find artists whose designs would grace the new money and filed a resolution.

Pocket-Sized Revolution.

Market Scene (University of Michigan,1910/1915)

Melecio, who responded to the call to symbolize our nation, submitted his designs in 1901. These designs were a result of his experimentation with medallions that he had created in the 1880s, and they were among his most exquisite works. His most famous design, which likely won him the bid, featured a beautiful woman holding a hammer and hitting an anvil with Mount Mayon in the background. This symbolized the steely will and hard labor of the Filipino people who are to carve their future; aptly named “Filipinas”.

The Philippine Commission loved the design and on December 18, 1902, prescribed Filipinas as the design that would be on the One Philippine Peso coin. When the new coin was released to the general public in March 1903, there was amazement with the artisanship of the female figure. Mary Fee, who was an American teacher in Capiz, wrote in her journal that the Filipinos were so impressed that there were cries of “Dios mio!” and “Hesus!”.

The nation had never seen such a thing before. They were used to seeing the faces of Spanish royalty, but never an icon that represented them as a whole. It was as if Melecio was telling the public that faith in the currency would equate to faith in the nation.

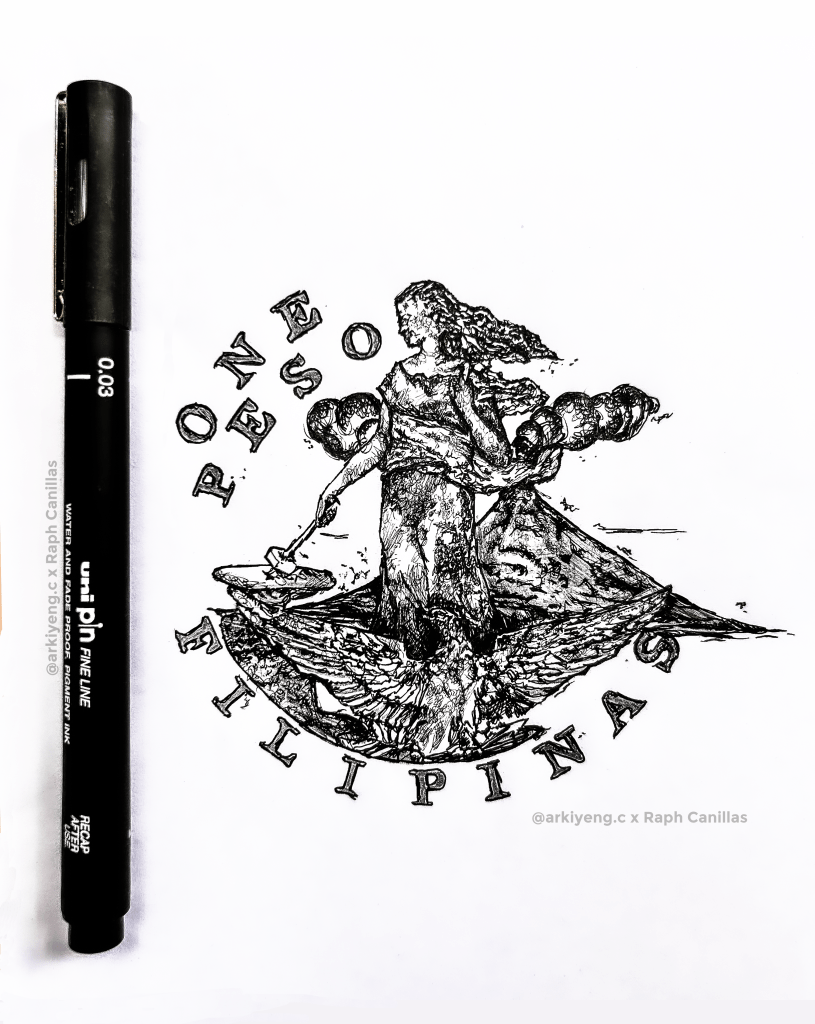

Filipinas (Raphael Canillas, 2023)

Melecio’s journey to this moment has been one of hardship and quiet triumph. Tuberculosis, a cruel companion, had lurked him for years, chipping away at his strength even as his imagination soared. Yet, fueled by a love for his people and a deep belief in their potential, he poured his soul into every line, every curve. Melecio’s design whispers the tale of hope and fortitude. That beautiful woman standing tall as her sarong catches the breeze, her gaze fixed on the hammer and anvil she must strike to forge her destiny.

These were not merely coins; these were the wills of farmers, merchants, students, and everyone whose spirit refused to be bent yearning for freedom. Death would claim Melecio after the release of the coins, but his soul lives on. The coin symbolizing the aspiration of the fledgling nation, moved across hands, whispering stories of a man who dared to forge a currency of hope.

Me.

Pay your artists well. Artists can create the connection of intangible cultural elements making them accessible and understandable. They act as the stewards of a nation’s heritage, preserving and transmitting cultural knowledge across generations. Art transcends linguistic and cultural barriers, fostering dialogue and understanding between nations. By sharing their unique perspectives and interpretations of heritage, artists humanize national narratives and connect people on an emotional level. In short, art enriches our lives, challenges perspectives, and sparks emotions.

All the drawings you see in this article were drawn by an aspiring artist, Iyeng Caringal (Arkiyeng.c). Check out her Instagram if you’re interested in her work!

It’s hard to imagine that one of the most venerable people of his time was buried in time. Prior to my research, I never knew that Melecio and his contributions existed. What’s most remarkable about him was that despite his socialite status in Spain, he decided to walk away from it all to aid in our country’s democracy. That democracy is well-sculpted and ingrained through the everyday use of the coin. May this article remind us of the artistic achievements of not only Melecio but every artist out there who strives to symbolize our nation.