This article is part one of a two-part series trailing the Philippine financial crisis of 1919.

Financial crises have longed shook the foundation of the Philippine economy. Through these tumultuous periods, the agriculture sector has long been a casualty and indicator of what’s to come. From the Philippine Debt Crisis of the 1980s to the Asian Financial Crisis of the 1990s, the industry had borne the brunt. Agrarian distress deepens as the sweat of Filipino farmers are undermined by currency devaluations, rapid inflation, and credit crises. This in turn amplifies poverty, exacerbating food security, and further widens the inequality gap.

Farming requires a significant amount of capital due to the labor involved and the risks associated with potential crop damage. For many farmers, access to such capital is a barrier as crop yields often lag behind the generation of income. Agricultural loans have been the most conventional way of obtaining capital and have a rich history dating back to the 1600s. It was only during the American period that these loans became institutionalized and played a significant role in kick-starting the industry.

Poking Holes for Harvest (University of Michigan, 1900)

In the face of financial crises, these challenges magnify, but they also catalyze movements for change. They compel a reevaluation of agricultural practices towards greater sustainability and inclusivity, offering an opportunity to reshape the landscape for the prosperity of all.

Agricultural Activity.

The Agricultural Bank of the Philippines (known today as the Philippine National Bank) was a key institution during the infancy of America’s colonization. At the time, this was the de facto central bank of the nation providing much-needed capital and liquidity. The Filipino hacienderos petitioned for a financial institution that would allow them to expand their agriculture ventures and export to the United States. The country’s previous colonizer, Spain, had left the industry in a state of decay as there were barely any initiatives to expand trade.

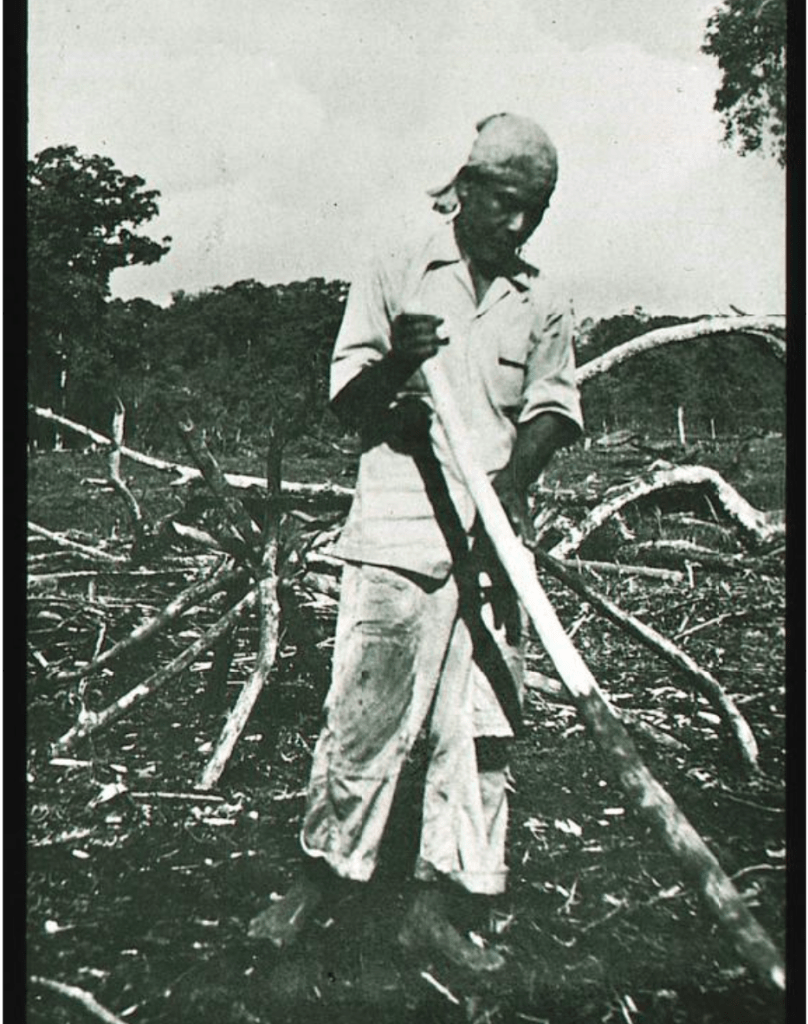

Public hearings were held in 1905 at Manila, Bacolod, and Iloilo to understand the public’s view on the state of the agricultural industry. Francisco Liongson, a doctor from Pampanga and an ilustrado, was a major advocate for the development of financial institutions. He noted that current law at the time forbade the government from investing in private ventures hindering support to the industry. Establishing the proposed bank was necessary to reinvigorate the industry by providing cheap and reliable debt.

Francisco Tongio Liongson (Fernando Guerrero, 1917)

The Philippine Commission recognized the need for the nation to have access to credit. The inherent lack of credit was detrimental, leaving fertile lands unproductive. There was much discussion in the American Congress regarding the agricultural state of their then-colony. Secretary William Howard Taft questioned the U.S. Attorney-General whether the Philippine legislature could enact a proposed law without Congress’s authorization to which he received an affirmative response. This pushed the legislature to act quickly and in June 1908, the legislature passed the Agricultural Bank Act.

Key details of the law included:

(1) Interest charged should not exceed 10% per month

(2) Loanable amounts are only between PHP 50 to 25,000

(3) A maximum tenor of 10 years to repay the loan

(4) About 50% of the loans issued should have par amount of PHP 5,000

(5) All loans are to be collateralized with real estate or mortgages

The passing of this law reflected the U.S. stance toward satisfying their needs as the colonizers and helping the broader Philippine society.

Banking on the Borrowers.

The first years of the Agriculture Bank saw sluggish operations due to stringent measures such as land titling and collateralization. Of the PHP 1 million appropriated for loan making, only about 5% were issued, disappointing the administration. Attempting to jumpstart operations required more lenient measures to entice businesses to take on these loans.

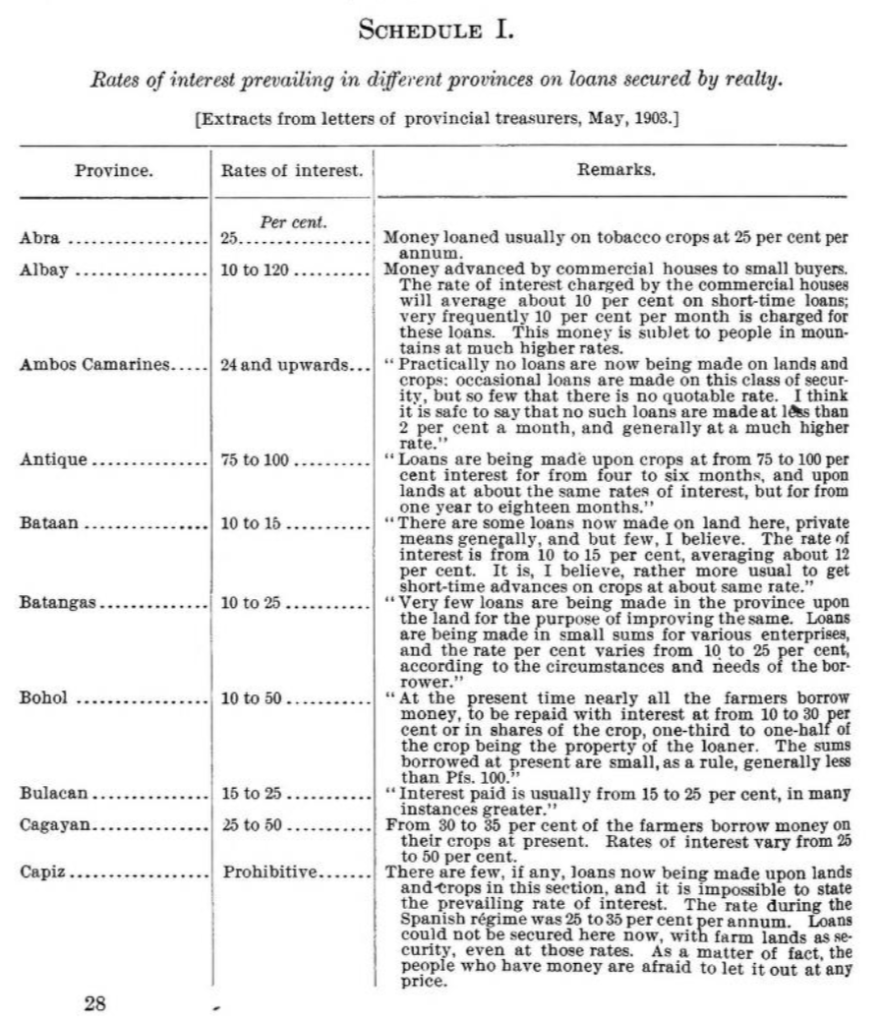

Existing Interest Rates on Agricultural Loans (Philippine Commission, 1906)

The Commission passed the law requiring the interest charged on loans to drop from 10% to 8% per annum provided that land titling wouldn’t be an issue. The yield change would also be applied retrospectively to foster good business relations with existing borrowers. The Commission also required the Bank to expand into underserved regions such as Zamboanga and Pampanga to create a presence and awareness of its services. Between 1909 and 1912, 12 new agencies were opened in these underserved regions.

Duck farming on the Pasig, near Pateros (University of Michigan, 1900)

By 1913, publicity and road shows created a boom for the Bank seeing a spike in loan issuance exceeding the appropriated amount. In five years, the agricultural loan business of the bank grew by 151% with most of these coming from the sugar producers in Negros Occidental and Pampanga. This was because the US had just provided preferential tariffs and businesses positioned themselves to push the commodity into the market.

Crisis Cometh.

The Philippine government became aware that the Bank had issued more loans than it was authorized to. To ensure sustainability and reduce the risk of insolvency, they scrambled to take action. The Bank required more cash to issue loans, and the only way banks could access that capital was through deposits. The Bank’s Board of Directors mandated that all government funds be deposited with them, and a portion of those funds be used to issue more loans.

Farmer and Kalabaw (University of Michigan, 1900)

Initially, it seemed like a smart move to use these deposits to improve the industry. However, the issuance of loans continued to increase, and they needed more funds. The Bank could not continue to grow loans without increasing the capitalization amount. It was discovered that the Bank had been inflating real estate appraisals to issue these loans, even when the properties’ values were lower. Most of these loans were given to the land owners, with little to no support for small farmers. The borrowers were also noted for using the loans to fund their personal lives, rather than their intended purpose. A crisis was coming.

Me.

Part one unveils the intriguing origins of the Agricultural Bank of the Philippines, now known today as the Philippine National Bank. They were the de facto central bank of the period functioning on behalf of the agricultural sector, epitomizing the belief in our nation’s industry to grow and compete. These agricultural loans were a financial commitment to enhancing our nation’s economic prowess.

With the ascent to great heights, the possibility of the fall looms. While I believe that loans can be a force for good, especially when used for societal advancement, the coming of the crisis is an alarm towards over-optimism and untempered ambition. The issuance of these loans was double-edged rooted in the desire for economic development and profit. Without the necessary capital market expectations and safeguards lead to economic peril. Only by learning from the lessons of the past can we hope to forge a more resilient and prosperous future for our nation.