Terminology Time!

The Balance of Payments (BOP) records all the financial transactions between a country and the rest of the world over a certain period. It’s a big financial “checklist” that tracks how money flows in and out of the country.

The balance of payments shows whether a country is financially healthy or if it’s borrowing too much or relying on foreign money. If a country earns more from exports or investments than it spends on imports or sends abroad, it has a “surplus;” if it’s spending more than it’s earning, it has a “deficit.”

Tropical Overheating.

The 1950s were in full swing as the Philippine economy roared, with the gross national product increasing by 7%. Agriculture and manufacturing, both cornerstones of the tropical island, grew by 7% and 11% on average. The latter saw a bull run as policy at the time favored local production over importation – high tariffs and import substitutions shielded the industry.

Philippine Farmlands (De Leon, 1965)

Despite economic growth, a few pillars were placed to ensure the sustainability of its progress. The manufacturing sector was dominated by US firms operating in final processing and packing sub-industries. They tended to have high operating costs and any profit would have to be remitted. Export earnings were heavily reliant on agricultural output and only due to increased area under cultivation. Both industries suffered from a lack of modernization and much-needed investment to grow. By the mid-60s, Philippine exports had stagnated and imports dramatically grew.

The Marcos Family (Ubagan, 2024)

Diosdado Macapagal, the President at the time, was marked by the rapid rise of the population without the necessary investment in job creation further slowing the economy. The rise of Ferdinand Marcos Sr. to the presidency sought to turn the situation around and adopted a debt-driven growth approach emphasizing public investment for the masses. In two years, public investment spending more than doubled fueled by low interest rates and easy credit policies. Put simply, the Marcos administration was able to afford loans for the sake of growth. Much investment was placed into the two industries to convert that debt-driven growth to one that would be export-led.

Marcos and his technocrats heavily monopsonized agricultural exports, particularly the coconut and sugar industries meaning that the government would be the single buyer to control the prices in the market. They believed that they could drive profit and export tax – all in the spirit of boosting local productivity and nationalistic industry. Manufacturing on the other hand still relied on protectionist policies. Interestingly, while production was local, more than half of the inputs were imported due to lower global prices. In total, imports still overpowered exports.

Given the trade imbalance, foreign exchange needs proliferated as heightened import demand took control. The Central Bank of the Philippines resorted to printing more money to finance the budget and trade deficit but would soon start to feel the heat.

Boiling Point.

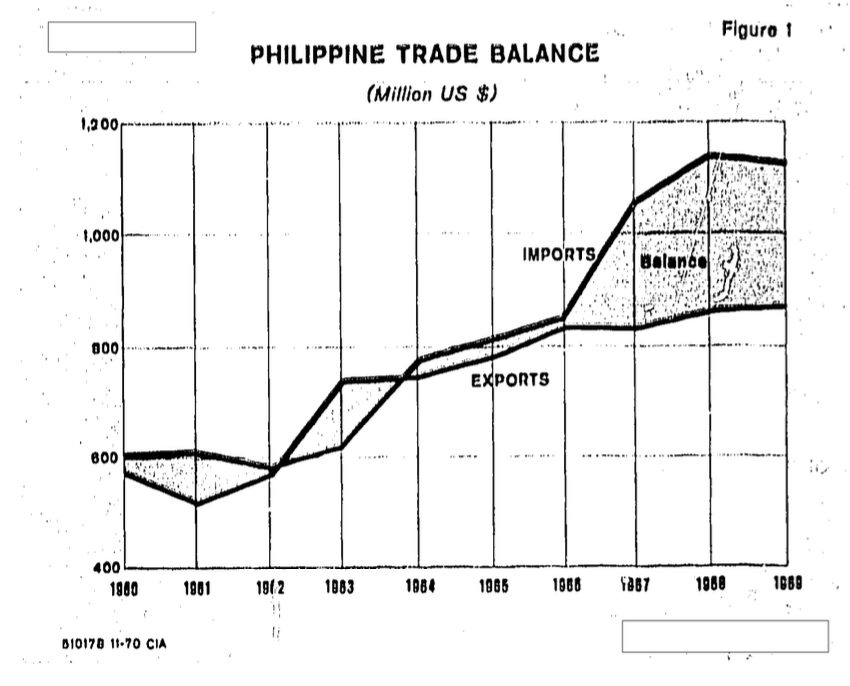

The first year of Marcos’ presidency seemed promising, with exports generating a $117 million surplus. However, things quickly took a turn for the worse. Over the next few years, the country’s balance of payments began to deteriorate. While the Philippines traditionally ran a trade deficit, the Marcos administration oversaw a significant worsening of this trend, with an average deficit of $270 million.

World demand for Philippine agricultural products waned as the failure to modernize took its toll. Sugar production suffered the most growing at an average of 2% causing it not to meet sugar quotas to the US market. The silver lining that the industry saw despite declining world demand was that export prices were rising otherwise boosting its nominal value.

Time series of the Philippines Trade Deficit (CIA, 1970)

Aware of the situation as early as 1967, the government resorted to borrowing at an average of $230 million. By late 1969, the total foreign debt reached $1.5 billion of which most were in short- and medium-term loans. The repayment schedule saw the government restructure its short-term debt to long-term to pay what was coming due – this was also funded with foreign exchange reserves that would soon draw the well empty. The boiling point came when the government racked up a bill clearly beyond the country’s capability.

Conflagration.

The nation’s financial position had deteriorated so much that the government postponed all repayments. With the trade imbalance worsening and foreign exchange reserves nearly depleted, a debt moratorium was provided. Debt was needed once again, however public and private creditors required that Marcos seek guidance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

While relief came through the IMF’s recommendation of rescheduling debt repayments, Marcos was forced to face the PHP devaluation by 43% and reduce tariffs. His government publicized that the new policies were effective and improved the balance of payments. In reality, the sharp rise in export value was still due to higher world prices and had little to do with Marcos’ financial reforms.

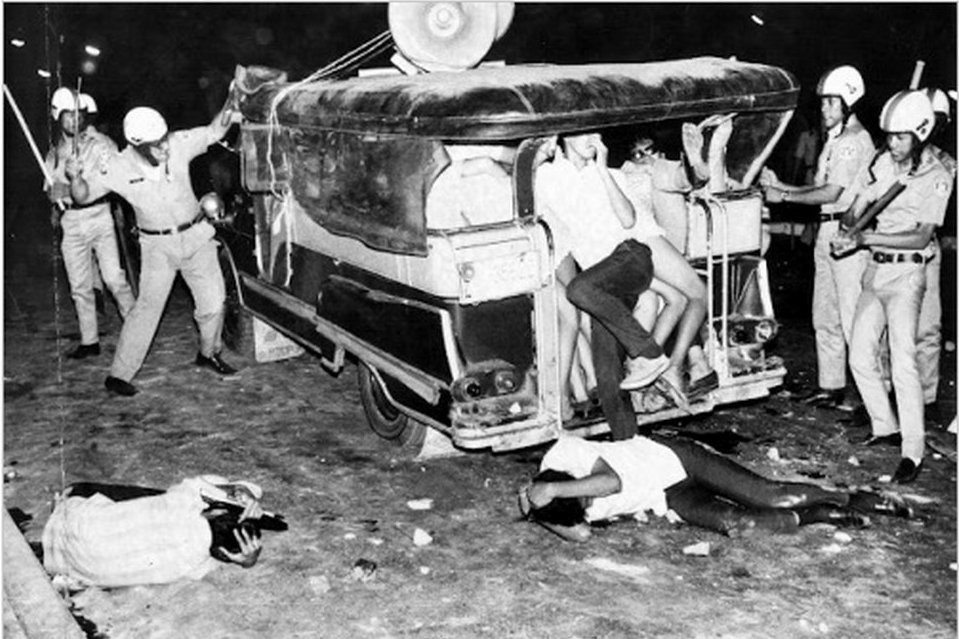

Rally Against Marcos in 1970 (Scalice, 2020)

A rapid decline in the standard of living saw consumer prices rise by 12% due to the increase in the prices of imported inputs in 1970. His restrictive financial policies and large PHP devaluation due to his debt momentum ultimately caused the nation to suffer slower growth rates, increased unemployment, and radicalism. Rallies occurred in Manila leading to the “First Quarter Storm”.

Police Brutality in Manila (Scalice, 2020)

Economists argue that the turmoil of which he started prompted him to run for reelection and that his campaign further exacerbated the situation as it was financed with massive money printing further devaluing the PHP. Eventually, Marcos would go on to declare Martial Law to institutionalize political discipline for economic prosperity. This never happened. At the very heart of it, calling back to the start of his first presidential campaign, his vision of a nationalistic industry burned right in front of him.

Me.

A tried and true saying about running a country is that a fiscal policy is only as good as its monetary policy. Marcos, eager to spur economic growth, embraced bold risks—yet these came at the nation’s expense. Ambitious infrastructure projects and institutional reforms marked his first presidential term, all framed as steps toward progress. But the real question arises when the tide of prosperity recedes: What happens when the money runs out, and the weight of debt comes crashing down?